A few years ago Nantucket, Massachusetts selected The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini as its One Book One Island Read. For middle-grade readers The Breadwinner by Deborah Ellis was chosen, and for younger readers, a picture book - The Librarian of Basra. A friend of mine, who helped select the books, told me that another islander spoke to her and insisted that the selection committee made a terrible choice, especially with the Librarian of Basra, which, she informed my friend, would make kids think that the U.S. had bombed Iraq! I am not sure whether the complainant didn't know that the U.S. had bombed Iraq, or if she simply didn't think kids should learn about such a thing. In any case, my friend informed her that the U.S. had, indeed, bombed Iraq.

This book tells the story of Alia Muhammad Baker, the Librarian of Basra, who removed all 30,000 books from the library in order to protect them. The library was burned down nine days after she removed the books. It is beautifully illustrated, and celebrates libraries not only as places for books, but where ideas are exchanged.

For more information see this story from the New York Times

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Sunday, May 29, 2011

The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet - by Reif Larsen

A novel about grief, youth, and science, with some history, some travel, and a bit of magic realism thrown in.

Twelve-year old T.S. (Tecumseh Sparrow) Spivet is surprised to receive a call from the Smithsonian Institution informing him he has been awarded the Baird fellowship, a prize he has never heard of, for his exceptional illustrations and maps. Sure that his parents will not allow him to go to Washington, and knowing that the Smithsonian has no idea that he is a child, he packs his bag and leaves his ranch one morning in order to hop a train from his hometown in Montana and head east and claim his prize. The novel is divided into three parts. The first tells of his preparations for going east. The second is about the journey, which turned out to be really more of an odyessey, complete with a "cyclops" attack in the form of an over-zealous preacher with a lazy eye who stabs our young hero when he reaches Chicago. The final part tells of T.S.'s time in the nation's capital. Throughout the work readers are drawn to the marginalia which are drawings, or sometimes sidebars that provide more insight into the prodigy's world.

Twelve-year old T.S. (Tecumseh Sparrow) Spivet is surprised to receive a call from the Smithsonian Institution informing him he has been awarded the Baird fellowship, a prize he has never heard of, for his exceptional illustrations and maps. Sure that his parents will not allow him to go to Washington, and knowing that the Smithsonian has no idea that he is a child, he packs his bag and leaves his ranch one morning in order to hop a train from his hometown in Montana and head east and claim his prize. The novel is divided into three parts. The first tells of his preparations for going east. The second is about the journey, which turned out to be really more of an odyessey, complete with a "cyclops" attack in the form of an over-zealous preacher with a lazy eye who stabs our young hero when he reaches Chicago. The final part tells of T.S.'s time in the nation's capital. Throughout the work readers are drawn to the marginalia which are drawings, or sometimes sidebars that provide more insight into the prodigy's world.

Twelve-year old T.S. (Tecumseh Sparrow) Spivet is surprised to receive a call from the Smithsonian Institution informing him he has been awarded the Baird fellowship, a prize he has never heard of, for his exceptional illustrations and maps. Sure that his parents will not allow him to go to Washington, and knowing that the Smithsonian has no idea that he is a child, he packs his bag and leaves his ranch one morning in order to hop a train from his hometown in Montana and head east and claim his prize. The novel is divided into three parts. The first tells of his preparations for going east. The second is about the journey, which turned out to be really more of an odyessey, complete with a "cyclops" attack in the form of an over-zealous preacher with a lazy eye who stabs our young hero when he reaches Chicago. The final part tells of T.S.'s time in the nation's capital. Throughout the work readers are drawn to the marginalia which are drawings, or sometimes sidebars that provide more insight into the prodigy's world.

Twelve-year old T.S. (Tecumseh Sparrow) Spivet is surprised to receive a call from the Smithsonian Institution informing him he has been awarded the Baird fellowship, a prize he has never heard of, for his exceptional illustrations and maps. Sure that his parents will not allow him to go to Washington, and knowing that the Smithsonian has no idea that he is a child, he packs his bag and leaves his ranch one morning in order to hop a train from his hometown in Montana and head east and claim his prize. The novel is divided into three parts. The first tells of his preparations for going east. The second is about the journey, which turned out to be really more of an odyessey, complete with a "cyclops" attack in the form of an over-zealous preacher with a lazy eye who stabs our young hero when he reaches Chicago. The final part tells of T.S.'s time in the nation's capital. Throughout the work readers are drawn to the marginalia which are drawings, or sometimes sidebars that provide more insight into the prodigy's world.For someone who must do a lot of research, T.S. doesn't talk much about going to the library. It probably isn't easy for him though, as he lives on a ranch, and can't just ride his bike to the public library after school. However, he does acknowledge sometimes riding with his father into town on Saturdays to go to the Butte Archives which were "crammed inside the upper story of an old converted firehouse...[and] could barely contain the haphazard array of historical detritus...[It] smelled of mildewed newspaper and a very particular, slightly acrid lavender perfume that the old woman who tended the stacks, Mrs. Tathertum, wore quite liberally." T.S. describes a "Pavlovian" reaction to the smell of the perfume which "instantly transported back that feeling of discovery, the sensation of fingertips against old paper, whose surface was powdery and fragile, like the membrane of a moth's wing." This passage really celebrates what archives are - true places of discovery, where any researcher may uncover some unknown artifact and experience a real sense of wonder in its age, and ponder who saved it in the first place, and why.

There are two side bar entries about books he checked out from the Butte Public Library. One of them mentions the classic children's book From the Mixed Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler. I can't remember where else I heard that book mentioned recently, but seeing it here made me think it has achieved some sort of legendary status. Even those who haven't read it, have probably at least heard of it.

While T.S. is on the train he passes some of the time reading a journal his mother wrote - a fictionalized account of his ancestry. It is in this journal that we learn that his great-great grandmother, Emma Osterville, completed her dissertation using the "libraries down at Yale".

While libraries are not heavily commented upon in this work, it is clear that T.S. recognizes their importance, and enjoys them when he can.

Tuesday, May 24, 2011

Invisible Privilege: A Memoir about Race, Class, and Gender - by Paula Rothenberg

Author Rothenberg examines her life as both a perpetrator, and victim, of privilege while growing up in a weathy Orthodox Jewish family in New York, then as a college student, as a professor, and as a parent. Unaware of her privilege as a child she simply accepts things as they are. A succession of black cleaning ladies is just ordinary life to her. She also learns as a young child not to tell when she is victimized by a sexual predator, a tough lesson with consequences she will face much later in life when it prevents her from earning her doctorate. As an adult she looks back on these experiences and sees them through different lenses.

Author Rothenberg examines her life as both a perpetrator, and victim, of privilege while growing up in a weathy Orthodox Jewish family in New York, then as a college student, as a professor, and as a parent. Unaware of her privilege as a child she simply accepts things as they are. A succession of black cleaning ladies is just ordinary life to her. She also learns as a young child not to tell when she is victimized by a sexual predator, a tough lesson with consequences she will face much later in life when it prevents her from earning her doctorate. As an adult she looks back on these experiences and sees them through different lenses.There is a lot about reading, and books, in this memoir. Education, to varying degrees, was important to Rothenberg's family and she was encouraged to read by her mother, who was also an avid reader. Most of the early passages about books though, are about purchasing, or owning books, although she does say that her grandmother used Womrath bookstore's "lending library" to read countless mysteries. She also tells of her summers spent at the family's second home in Connecticut, when she was "allowed...to buy stacks of books to see [her] through until school began again" and admits that "to this day, books are the one thing I can buy without any feelings of being extravagant" (p.65). Late in the work however, while describing her suburban home in New Jersey and her children's schools she recognizes that the schools in the "white neighborhoods" were the ones with "new science laboratories, extensive libraries, and well-equipped gyms and caferterias" (p. 206), and that children of privilege will have parents who have time to volunteer in the school library, and in fundraising efforts to buy more books. (It is also true that these same parents can afford to buy books for their children - not that a bookstore is any substitute for a library!) It is a sad truth that too often libraries are places for the privileged, and it grows ever more true as libraries become easy targets for budget cuts. (See my post on defunding libraries.)

A final look at libraries comes almost as an afterthought when she describes taking her young daughter to the public library to do some research on poet Paul Laurence Dunbar for Black History Month. She seems to think of going to the library only after exhausting all the resources she has at home. They do find some information, but are not surprised that there are no children's books about him. In a follow up visit (many years later) she does discover some books on Dunbar in the Children's Collection. Let it never be said that librarians do not respond to the needs of their communities.

Find out more about this work at http://www.kansaspress.ku.edu/rotinv.html

Monday, May 23, 2011

On this day in library history

One hundred years ago today President William Howard Taft dedicated the New York Public Library, along with Governor John Alden Dix, and Mayor William Jay Gaynor.

I attempted to visit this library a few years ago while visiting NYC and was impressed with the sidewalk leading up to it, which had all kinds of pro-library messages, and was also duly impressed by the big lions that are the icons of this institution. I was completely disappointed upon entering. I had hoped to talk to a reference librarian but found the security guards, metal detectors and general aura so indimidating (the place didn't even look like a library) that I walked right out. Where were the books? Where are the people pursuing knowledge? It was the total antithesis of what I had been taught libraries should be.

I attempted to visit this library a few years ago while visiting NYC and was impressed with the sidewalk leading up to it, which had all kinds of pro-library messages, and was also duly impressed by the big lions that are the icons of this institution. I was completely disappointed upon entering. I had hoped to talk to a reference librarian but found the security guards, metal detectors and general aura so indimidating (the place didn't even look like a library) that I walked right out. Where were the books? Where are the people pursuing knowledge? It was the total antithesis of what I had been taught libraries should be.

Librarians at the Gate

Librarians all over the country regularly read PW (Publisher's Weekly) magazine, perhaps not so much for information on publishing trends, as to see what the bestsellers are, and read the book reviews. I rarely read the articles myself, as most feature publishers or booksellers. A recent issue, however, had this article about librarians at Book Expo America, and the quandries facing them when faced with e-book purchases. Libraries wish to serve their patrons by keeping up with demand for e-books, which grows exponentially. Some publishers will not sell to libraries at all, or limit how many times an e-book can circulate, fearing that providing the e-book format to libraries "would turn 'legions of buyers into borrowers'". I don't even understand that. If that were true wouldn't it be true of hard copy books as well? Why don't the publishers stop selling those as to libraries. The truth is libraries do buy a lot of books, and if more people are looking for e-books, librarians will buy more of them. E-book publishers should be wooing librarians.

Friday, May 20, 2011

Field Days: A Year of Farming, Eating and Drinking Wine in California by Jonah Raskin

In 2009 I wrote a blog called "My Year of Reading 'Year of' Books" in which I read and wrote about books that were part of the stunt lit genre where authors spent a year making some change in their lives, and documenting it. For the most part, I really liked those books, and although my own "year of" project is over, I still look for books in this category. In the case of Field Days, the theme actually cross pollinates on three of my blogs. In addition to this one, my husband James wrote a post about it on our food blog "Una Nueva Receta Cada Semana". James and I read this one out loud to each other, we had started back in January and finally finished last night.

Raskin spent a year visitng farms, farmer's markets, wineries, and restaurants, mostly in Northern California, and spoke, and worked, with farmers, vintners, migrant workers, chefs and others who were part of the local/organic/slow food movement. He worked retail at the Red Barn Store at the Oak Hill Farm and also harvested crops. The pace of the book is slow, as it should be, and probably why we took so long to read it. We found reading this to be soothing.

Author Jack London figures in this book throughout and it is through him that we find our first library mention when we learn from "...Kevin Starr the California historian and for many years the California State Librarian [that] 'the Sonoma chapter of Jack London's life, his last chapter, dramatized a modality of California madness'". (p. 60).

The importance of libraries for research is highlighted in a passage about agribusiness in which Raskin writes of Carey McWilliams classic 1939 work Factories in the Field which "went so far as to denouce 'the rise of farm fascism'". The book was based on "his own observations of the horrendous labor conditions in the San Joaquin Valley in 1935 and on extensive library research". (p. 195)

Two mentions of "personal" libraries appear. One in the body of the work where Raskin describes the connection between food and sex in the books Consider the Oyster and The Gastronomical Me, both by M.F.K. Fisher which he says are "now a permanent part of [his] library" (p.154). The other personal library is noted in the acknowledgements "Don Emblem looked through his vast library and found books for me to read on the subject of farming and nature..."

Even with only these four brief notes about libraries Raskin shows that books (and librarians!) really are our friends.

More about the author at http://www.sonoma.edu/users/r/raskin/index.htm.

Thursday, May 19, 2011

Defunding School Libraries will not Solve Economic Problems

Librarians are teachers. No matter what specialization they have, no matter whether they work in school, public, academic, or other specialized setting, their jobs entail helping others to find the information they need. It is increasingly disheartening to see libraries lose funding. When public libraries cut hours, or close branches, they are denying computer access to a person who needs to fill out a job application on line, and denying learning opportunities to all. When school libraries cut funding for trained librarians classroom teachers are left without collaborators on projects, and students are left with poor choices of materials for completing assignments. Underfunded libraries may also be ineligible for certains grants, which magnifies the problem. Additionally, recent studies have shown that students who go to schools with well funded libraries and full-time librarians score better on standardized tests, and get better grades. Skills, and love, for life-long learning are taught at the library.

The underfunding of libraries is a problem across the country. Read more from the National Education Association's article Checking Out; and American Libraries LAUSD doubts that seasoned teacher-librarians can teach.

The underfunding of libraries is a problem across the country. Read more from the National Education Association's article Checking Out; and American Libraries LAUSD doubts that seasoned teacher-librarians can teach.

Sunday, May 15, 2011

The Lost Gate - by Orson Scott Card

Let's call this one a "ringer". I found it browsing the Leisure Reading Collection at my library (we like to call them the "fun books"). The title was what originally intrigued me, but when I saw the cover illustration - hands holding an open book - and read inside book jacket which alluded to a library, the deal was done.

Once Danny realizes that he is a "gatemaker" he knows his life is at stake, and runs away, where he finds other Orphans, magical folk who are not part of a family. This book not only mentions libraries so many times I stopped marking all the pages, it is in libraries that our hero often discovers new ways to use his magic. He first discovers how to purposely make a gate while hiding inside the wall of his family's library and realizes he has been discovered and must escape. Later he tests out his theory that he can create a gate and only pass part of his body through it while visiting the lavatory in the holy grail of libraries: the Library of Congress. It is here where he meets a great librarian who teaches him how to effectively use a search engine, and shows him a fabulous old book with information that starts him on his way to learning more about his gift. And it is here that readers are reminded that Danny is, after all, a 13-year old, when he moons a security guard. One other imporant mention of a library comes when we are reminded that we must pay for library books that are ruined. Danny's housemate Lana pees herself when he tickles her, when Lana's husband Ced picks her up and sets her on top of a book he admonishes them "[i]f that's a library book, they're going to make you pay a fine." Indeed, my friend. A bonus to this story for this Spanish instructor/Librarian is that Danny also has a penchant for languages: a skill that serves him well in the LoC.

Although Danny's greatest magical feat takes place in a high school gym, it is, of course, right and good that he learns so much in libraries prior to that. What Card illustrates is something that librarians see in their jobs everyday: libraries are magical places. It is so for children getting their first library cards; for scholars who find knowledge upon which to build; and for historians who uncover long forgotten archives. We need no gatemaker to open the door for us, the magic is there for us to discover ourselves.

Sunday, May 8, 2011

On this Day in Library History

Saturday, May 7, 2011

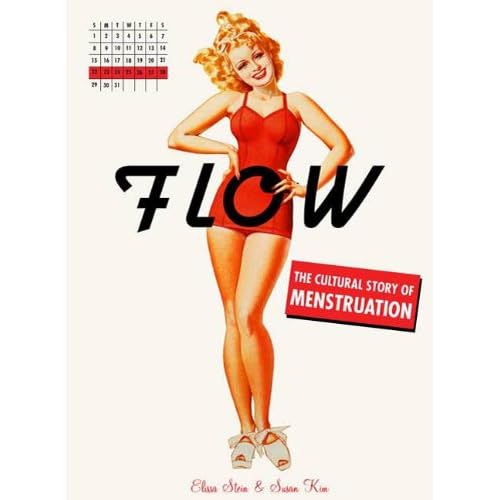

Flow: The Cultural History of Menstruation - by Elissa Stein and Susan Kim

An interesting and quirky book about the marketing of feminine hygiene products, Flow was actually pretty fun to read. It also made me feel strangely nostalgic as I recognized ads and pamphets from my teens and twenties. Since the book covers almost a century of marketing, women of all ages are likely to see something familiar here. Making the point that men do not have anything like a uterus as part of their anatomy (everything else we can find some kind of similarity with) periods have really not been studied much, which is why so many myths about them persist. The authors acknowlege "the informative staff at the New York City Public Library Picture Collection", as well as Mitch Evans of Ad* Access, at Duke University Libraries. The only mention of libraries within the body of the work, though, is really the just the idea of a library where the authors say "...what we still don't know about menstruation could fill a small library" (p. 186).This may seem not even worth a blog post, but it has always been my tradition in my previous blogs to include any mention of libraries. I also think that in this case, the way it is used illustrates a kind of importance about libraries in our culture. At a time when rumors abound that libraries are going away, this not insignificant use shows how deeply ingrained libraries are in our culture. The authors could not have used this image if they did not believe that their readers would know what they meant by it.

An interesting and quirky book about the marketing of feminine hygiene products, Flow was actually pretty fun to read. It also made me feel strangely nostalgic as I recognized ads and pamphets from my teens and twenties. Since the book covers almost a century of marketing, women of all ages are likely to see something familiar here. Making the point that men do not have anything like a uterus as part of their anatomy (everything else we can find some kind of similarity with) periods have really not been studied much, which is why so many myths about them persist. The authors acknowlege "the informative staff at the New York City Public Library Picture Collection", as well as Mitch Evans of Ad* Access, at Duke University Libraries. The only mention of libraries within the body of the work, though, is really the just the idea of a library where the authors say "...what we still don't know about menstruation could fill a small library" (p. 186).This may seem not even worth a blog post, but it has always been my tradition in my previous blogs to include any mention of libraries. I also think that in this case, the way it is used illustrates a kind of importance about libraries in our culture. At a time when rumors abound that libraries are going away, this not insignificant use shows how deeply ingrained libraries are in our culture. The authors could not have used this image if they did not believe that their readers would know what they meant by it.Friday, May 6, 2011

You Don't Look Like Anyone I Know - by Heather Sellers

Heather Sellers has a rare neurological condition called prosopagnosia, or face blindness. She is unable to recognize people by their faces. Her memoir is the story of how she found about about the disorder when she was late in her thirties, and came to terms with it, as well as her roller coaster childhood with a schizophrenic mother and cross-dressing, alcoholic father. The book is fascinating, and as a college writing professor, Sellers clearly understands the importance of libraries - she invokes them on no fewer than 11 occasions. In some cases the library is simply a backdrop, a place she mentions in passing, but in other cases the library is an important turning point, an active character who helps Sellers in her self-discovery. The first instance of this is when "...the librarian at [her] university introduced [her] to PsycLIT" and she begins to search for conditions that describe her. I really enjoyed reading this part. Sellers made it clear that doing research is a sloppy business, and that finding the right search terms takes some trial and error, but once she hits on the right thing, a world of other information opens up to her. Libraries are used as part of her college life fantasy (indeed!); where she goes to learn about child care for her babysitting jobs; where she finds out how to get a do-it-yourself divorce; and finally where she goes when she wants to see what Da Vinci's drawings look like, and finds out he actually wrote about face recognition. I very much enjoyed reading this book, I learned a lot, and thrilled to see it was so pro-library.

To learn more about Heather Sellers, and read an excerpt of the book, see this NPR story. To find out more about face blindness see http://www.faceblind.org/research/

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)