Thursday, October 11, 2018

The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For - by Alison Bechdel

Baltimore County Public Library's #BWellRead challenge for September 2018 was to "read a book you've always meant to read". I wasn't sure how to interpret "always" but I looked back on the list I've been keeping since about the start of this century and decided that a book that's been waiting ten years to be read qualified.

I made several attempts to purchase this at an independent bookstore, which it turns out would have been appropriate since much of the action takes place in such a store. Ultimately, however, I caved and ended up getting this from Amazon. I do offer myself some absolution though as I bought something at each of the independent shops I visited.

Although this reads as a graphic novel it is, in fact, a collection of the Dykes to Watch Out For comic strips. The book includes strips originally published between 1987-2008. While each panel features an independent episode, it reads as a soap opera with characters falling in and out of love, changing careers, becoming parents, and negotiating the evolving political landscape. I had not thought about some of the old political issues that come up in this work for a long time, and likewise was reminded how long some of the stalwarts in Washington have been around making trouble. It was sort of like visiting an old "frenemy".

Despite the fact that the characters in this work are quite well read, it was not until about the midway point of this 390-page book that I found any mention of libraries at all, and it was in a fantasy sequence. Each of three roommates (Ginger, Lois, and Sparrow) imagines what it would be like to live without the other two. Ginger's daydream involves a well organized bookshelf "in Library of Congress order". I then had to read another 80-ish pages before a library comes into play again, this time for real. Mo and her paramour Sydney do it "by the book" (so to speak) right there in the HQ 70s in the University Library (the range that includes books on lesbianism). It is no doubt the excitement of this tryst that prompts Mo to apply to library school, something we discover on the very next page! It is at this point that the libraries just keep coming as we follow Mo through her acceptance, taking classes, graduation, and getting her first job - in a post PATRIOT act world.

I am posting this one in honor of National Coming Out Day.

Wednesday, October 10, 2018

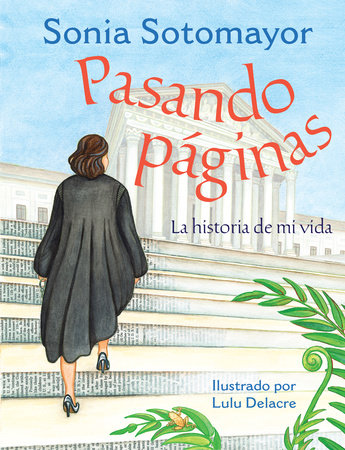

Pasando páginas: La historia de mi vida - por Sonia Sotomayor

This is my second blog post this year about Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor. In June I posted about Jonah Winter's bilingual book Sonia Sotomayor: A Judge Grows in the Bronx=La juez que creció en el Bronx in honor of Sotomayor's birthday. This one I read in honor of the convening of the Supreme Court on the First Monday in October.

Even more "book centric" than Winter's work this book starts out with the line "Mi historia es una historia sobre libros..." (My story is a story of books...). Sotomayor goes on to describe how books, of all genres, influenced her and aided her in learning English, as well as how books helped her to grow, imagine, and learn.

Sotomayor's father died when she was only nine years old. She describes how her local library (Parkchester Library) became a refuge for her, a place where she could feel "consuelo y tranquilidad" (comfort and tranquility). As well she felt "dischosa" (fortunate) that the library was so close to her home that she could walk there. Similarly, as a college student at Princeton University she finds her way to the Firestone Library where

los libros se convirtieron en el salvavidas que me ayudaba a mantener la cabeza fuera del agua.

(the books became a lifesaver that helped me to keep my head above water).On one of the final pages of the book Sotomayor eloquently reminds us that

Los libros son llaves que desvelan las sabiduría del ayer y abren la puerta del mañana.

(Books are the keys that uncover yesterday's knowledge and open tomorrow's door).This book is written in Spanish, although an English version (Turning Pages) is available.

Tuesday, October 9, 2018

The Living Wake-the movie

My husband has a habit of looking up movies (as we're watching them) on The Internet Movie Database (imdb.com) and telling me what other venues the actors and actresses have played in. Earlier this year while we were viewing season two of The Handmaid's Tale on hulu he informed me that Ann Dowd (Aunt Lydia) played a librarian in a film called The Living Wake, at which point I immediately added it to my Netflix list. I'd forgotten all about this conversation until last night when we watched said film and the library scene came on. James looked up The Living Wake on imdb and asked if I knew who the librarian was. I said she looked familiar, but couldn't place her and when he told me she was Aunt Lydia, our previous conversation came back to me and the entire episode came full circle.

The premise of this film is that self-proclaimed genius K. Roth Binew (Mike O'Connell) discovers that he has some dreaded, as yet unnamed, disease and has been told of the exact date and time of his death. In his final day he plans his own wake and invites a band of rather eccentric people to join him for his last performance. He is aided in this endeavor by his sidekick Mills (Jesse Eisenberg) who employs a rickshaw to transport K. Roth to his various destinations. One of these is the public library where K. Roth attempts to donate the five (unpublished) books he has authored. He is thwarted by the nameless librarian, a shushing bunhead, who informs him that she cannot accept donations. She explains that there is a process and that all books must be approved by the board. She, as a mere know-nothing librarian, has no authority to choose books. Furthermore, she says, that the public cannot be trusted to select its own materials otherwise "this place would be brimming with pornography and gun magazines". And although K. Roth admonishes her to "flex your muscle and abuse your power" she shuns his advice reminding him that "the rules are the rules".

This film is not so much sentimental as it is irreverent. It will likely appeal to those who liked Moulin Rouge! or Big Fish. It is a must-see for those who are interested in librarian films, but be aware that those looking for a film that passes the Bechdel Test will not find it here.

Monday, October 1, 2018

Writing with Intent: Essays, Reviews, Personal Prose 1983-2005 - by Margaret Atwood

My husband and I read this collection of Atwood's writings over an eight-month period. Thought provoking, as well as conversation provoking, we both just felt smarter each time we read some of this work.

Atwood gives libraries and librarians their due in various essays - starting with the Introduction

As one early reader of this book pointed out, I have a habit of kicking off my discussion of a book or author or group of books by saying that I read it (or him, or her, or them) in the cellar when I was growing up; or that I came across them in the bookcase at home; or that I found them at the cottage; or that I took them out from the library. If these statements were metaphors I'd excise all of them except one, but they are simply snippets of my reading history. My justification for mentioning where and when I first read a book is that...the impression a book makes on you is often tied to your age and circumstances at the time you read it, and your fondness for books you loved when young continues with you through your life.This custom of telling of the history of reading a book is something that can be found in my blog as well. I often begin my posts by saying where I found a book, or when I first read it. There is in fact something rather meta in my description of my first encounter with Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale when I consider it in light of what Atwood says here. And in honor of this tradition, I will divulge that I checked this book out of the Maxwell Library, the one in which I work. I picked it out specifically because I wanted to read Atwood, and this seemed like it would be a good read along with my husband.

Atwood gives a shout out to librarians and archivists as "guardian angels of paper" in her essay "In Search of Alias Grace".

Without them there would be a lot less of the past than there is, and I and many other writers owe them a huge debt of thanks.This was written in 1996, and seems to set up her comments in a later work - a review of A Story as Sharp as a Knife: The Classical Haida Mythtellers and Their World by Robert Bringhurst (2004). Bringhurst's book tells of two poets Skaay and Ghandl who were from Haida "one of the many cultures that flourished along the northwest coast of North America before the arrival of the smallpox-carrying, Gospel-bearing Europeans in the nineteenth century." The two survived the disease, but were left blinded. They told their stories, in the original Haida language to John Reed Swanton, an ethnography/linguist who was "collecting stories as a way to learn a language." The poets died in the early twentieth century and "their stories gathered dust in libraries for almost a hundred years" before Bringhurst found them and over a twelve-year period taught himself the language and wrote a book about it.

It is a good thing we have archivists and librarians, otherwise we wouldn't know this story at all.

In her discussion of author Dashiell Hammett Atwood laments the lack of a library in northern Canada where she spent her preadolescent summers, and informs the readers that she, therefore, had to re-read a lot of detective fiction. Where she found Erle Stanley Gardner, or Ellery Queen "dry", Hammett's writing was, conversely, "fast-paced, sharp-edged, and filled with zippy dialogue." We also learn that "as a boy [Hammett] wanted to read all the books in the Baltimore public library". I imagine she means the Baltimore City library, rather than the Baltimore County library, which is where I got my first library card. Nevertheless, this bit of trivia gave me a special thrill.

Atwood describes her foray's into Harvard's Widener Library as a graduate student in the 1960s in her Introduction to She by H. Rider Haggard

Once I was let loose in the stacks, my penchant for not doing my homework soon reasserted itself, and it wasn't long before I was snuffling around in Rider Haggard and his ilk...In her introduction to "The Complete Stories, Volume 4 by Morley Callaghan" we learn that Callaghan's books were

sometimes banned by the public library in Toronto - I forget what the rationalization was, but the real reason could only have been that if a Canadian were to do anything so ethically dubious as write, he should at least write like a proper colonial and not like someone who had lived in the Paris of Joyce and Gertrude Stein.Totally appropriate that I'm writing about this during Banned Books Week.

And speaking of banned books, Atwood's review of Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books by Azar Nafisi begins with the question of where to categorize such a book. After making, and rejecting several suggestions she says

A mischievous soul might stash it under "book groups," which would be about as close as my college library's choice of "veterinary medicine" for Hemingway's Death in the Afternoon.This same kind of questioning of classification is used in her review of W.S. Merwin's The Mays of Ventadorn. She clearly understands the kind of struggles cataloging librarians face when she recognizes that

It is...the sort of book that poses a problem for classifiers: What shelf to put it on? Is it a memoir? Not exactly, but sort of. Is it a rumination upon memory? Yes and no. It is about poetry? Not only.I image that not everyone will read this book cover to cover. I expect many scholars will likely read the most relevant parts for their specific research and then return the book to the shelf.

But those who decide to take the deep dive will be richly rewarded.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)