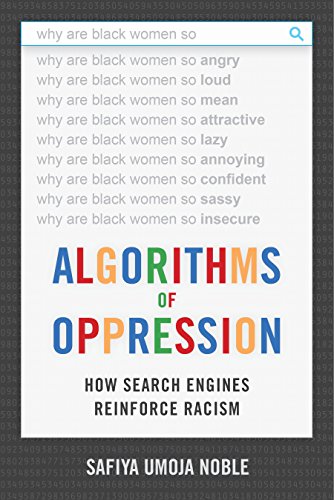

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina (one of the most devastating natural disasters of the 21st century) my husband learned an important lesson about doing Google image searches in front of a class. Typing in "Katrina" into the search box he (and the class) were bombarded with pictures of buxom women. This was literally just days after the hurricane struck and news of horrific flooding and drownings were still the top news stories of the day. Noble explains that similar results are returned when one types in the words "black girls".

However much we might want to believe that machines will provide neutral results, the fact remains that algorithms are written by people (mostly young, white men) who wittingly or not, program in their own biases.

My own research on Google and heuristics demonstrates exactly what conventional wisdom tells us: that people are more likely to click on links that appear at the top of a search result list. If people don't see what they want they assume it isn't there. It is very unlikely that someone will look beyond the first screen of results.

This is not only a problem in Google, but in library databases as well. Providing the example of searching the term "black history" in the ARTstor database the author shows a result page full of European and White American artists.

There was a lot to say about libraries and librarians in this work. In some places there is praise for our work, and recognition of our value. In others the author offers fair criticism and suggestions about where we can do some reflection and reparation where outdated language and systems are used.

A few years ago, I gave a presentation in which I compared librarians to colonizers. By creating an ambiguous and arbitrary system of organization and classification, and putting ourselves in charge of it, and, furthermore placing those on the margins in a position that requires them to come to us for assistance we are regulating knowledge, and determining who gets a piece of it. Noble goes even further explaining how the Dewey Decimal System itself, along with the standardized subject headings, were created so as to oppress. Citing the work of Hope A. Olsen from the the School of Information Studies at the University or Wisconsin, Milwaukee Noble explains that

Those who have the power to design systems - classification or technical - hold the ability to prioritize hierarchical schemes that privilege certain types of information over others.

As recently as 2016 the term "Illegal Alien" was being used as a Library of Congress Subject Heading (LCSH). Students at the Dartmouth College were successful in their bid to have the term removed. The headings "Noncitizen" and "Unauthorized Immigration" are now used. The move was not without controversy and included a threat to the funding of the Library of Congress in the form of HR 4926 "Stopping Partisan Policy at the Library of Congress Act". Librarians have recognized our own use of outdated and offensive language before, replacing the heading "Jewish question" with "Jews" and "Yellow Peril" with "Asian Americans".

Privilege and bias are also evident in the Dewey Decimal Classification system. For instance over 80% of the 200 range numbers is used for Christian religions although only about a third of people worldwide identify as Christians.

Librarians, however, also can be credited for discovering and resolving some of these problems. I was reminded of this article, recently shared with me: Remembering the Howard University Librarian who Decolonized the Way Books were Catalogued". It is important to note that the librarian was a woman of color, highlighting the necessity of a diverse population when designing and creating systems.

In her conclusion Noble envisions a new type of search engine, one in which

...all of our results were delivered in a visual rainbow of color that symbolized a controlled set of categories such that everything on the screen that was red was pornographic, everything that was green was business or commerce related, everything in orange was entertainment, and so forth. In this kind of scenario, we could see the entire indexable web and click on the colors we are interested in and go deeply into the shades we want to see...In my own imagination and in a project I am attempting to build, access to information on the web could be designed akin to the color-picker tool or some other highly transparent interface, so that users could find nuanced shades of information and easily identify borderlands between news and entertainment, or entertainment and pornography, or journalism and academic scholarship.This is indeed an ambitious project, and I would add that all caveats for design would apply. Such an undertaking would need a large, diverse group of people to categorize. As well I would be cautious about cutting into the autonomy of the users. What is pornography to some is art to others. Letting an algorithm decide what is scholarship and what is journalism can also be problematic. Some scholarship isn't really scholarship, and some journalism isn't really journalism. No matter what search engine is used everyone should use deliberation and do their due diligence in making selections about sources.

On the final page Noble reminds us that

Now more than ever we need libraries, universities, schools, and information resources that will help bolster and further expand democracy for all, rather than shrink the landscape of participation along racial, religious, and gendered lines.